I have been thinking about creating a new project for a while, one that abandons a lot of my previous style where I needed to support old compilers, operating systems, etc. I have no idea where this project leads, but it is something of a playground to approach the state-of-the-art as I see it. Using the latest features in C++, CMake and other parts of the ecosystem. It is targeting my preferred development environment which is a completely up to date Arch Linux desktop and other places may catch up at some point or this may be generalized to work more widely.

Modern?

I pondered a little on what means in a few previous posts and how quickly modern becomes outdated. Here I am looking more at what is barely working now that I can actually explore, and thinking about what I would do if I were creating a new project from scratch today. I will do that by creating a new project from scratch! It may not be perfect, and it will hopefully be something I can give enough time to evolve as I learn. The reference material is sparse as a fair bit of this is new or quite recent.

C++ Modules

A recent blog post described the new CMake C++ module support being made generally available in the latest 3.28 release. At its core this adds features to a very small subset of generators and compilers to enable the use of the new modules added in the C++20 standard. For the observant among you yes this post is being made in 2024 and the CMake post is from October 2023 and even with a rolling release distro such as Arch Linux it is only just supported using CMake 3.28, ninja 1.11 and clang 16!

Anyway, back to what we want. A new form of C++, a major evolution of the language whereby the way libraries export their interfaces and the way clients consume them changes. This is really why this has taken so long, and whilst I have understood the core concept for years, and worked on some Fortran codes that used modules that many of these concepts are inspired by I wanted to understand the details.

Interfaces

At the very core this is about programming interfaces, something I have been passionate about throughout my career. It is something I think I have been able to improve, but it was always frustrating that many of the things I did were not a part of the language. At the core C++ libraries export their interface using headers, with implementation files keeping the implementation separate. This has led to people like me becoming very skilled at using approaches such as PIMPL, forward declarations, limiting includes, crafting what ended up in headers and implementation files. Even using private headers to reduce the API surface, considering the ABI, and related areas.

When you include a header the preprocessor just copies that header (and every header it includes) into your source file and compiles it as a basic level. It sees everything at that point that is in the headers and later the linker checks that all symbols referenced can be resolved. So since C and C++ came into existence we have all used header guards to ensure this only happens once and felt like we did our best and moved on. In big projects this can end up being quite slow, and so things like precompiled headers have been added to try and reduce the issue.

#include "core.h";

int main() {

core::ello hello;

hello.hello();

return 0;

}

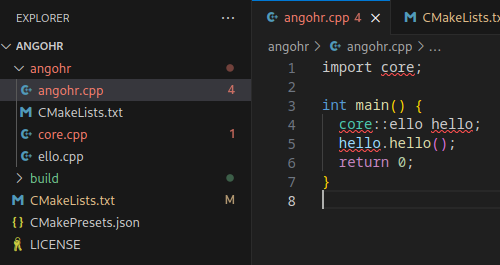

The above is how you might consume a very simple library that had a class called ello in the core namespace. Most projects have rules, such as only one class per header, matching the class name to the header file name etc to make things more logical and avoid over reliance on other parts of the project. Modules change this in what looks like a very minor way.

import core;

int main() {

core::ello hello;

hello.hello();

return 0;

}

This moves a lot of the responsibility for API from the preprocessor and header-implementation split into the build system and compiler machinery. You still need to link to the correct objects or library for symbol resolution, but now the compiler and the build system need to figure out where this module core comes from, what the correct build order is, and what is visible to the calling code. It also makes modern C++ code look just a little bit more like Python to the casual reader :-)

Building a Module

Building my very first module one of the nice things is that I can roughly halve the number of files in my project (at least in theory). So below is the very minimal version of a named module, note that I used a namespace that matches the module name, you don’t have to, and that is one thing that looks pretty odd to me upfront - the module name “disappears” pretty quickly as all exported API becomes part of the default global namespace.

module;

#include <iostream>

export module core;

namespace core {

export class ello {

public:

ello();

void hello();

};

ello::ello() = default;

void ello::hello() {

std::cout << "Why hello!\n";

}

}

There are a few things to unpack here, several were covered in the CMake post I linked to above. The huge thing is that all of this lives in core.cpp and I use the module keyword at the top to declare this as a global module so that I can use normal includes. I then declare that I am exporting a module called core. Then I open up a namespace of the same name and export a class called ello that I can call from the outside. The build system and compiler take care of linking that named module to this file so that when I import it the build order will be correct such that the module is available at compile time of consumers.

The CMake code is relatively simple but you do need to use just the right set of incantations with the right compiler and generator.

add_library(core)

target_sources(core

PUBLIC

FILE_SET CXX_MODULES FILES

core.cpp)

add_executable(angohr angohr.cpp)

target_link_libraries(angohr PRIVATE core)

This adds a library as normal, but then adds the module file to a special file set. It then links the executable to the library that contains the module. We are still very much at the toy C++ module stage of things but it is a start and it works for me locally. Who knows - it may work for you too! I find the default of the class being accessible in the global scope surprising coming from a few years of doing more with Python import statements but I think as a library developer it is easily solved by conventions such as the one I just used.

Separate Module Files

This is about as far as I will take it today, but the example above left me thinking that nothing but the simplest of libraries would be implemented in a single file. It looks like there are a few choices here, the one I would favor matches that old convention of a single class per file. So splitting my tiny module into two files, one that exports the entire module and another exporting the class. So core.cpp becomes:

export module core;

export import : iface.ello;

The ello.cpp then takes on most of the code:

module;

#include <iostream>

export module core : iface.ello;

namespace core {

export class ello {

public:

ello();

void hello();

};

ello::ello() = default;

void ello::hello() {

std::cout << "Why hello!\n";

}

}

This can still be called from the client in exactly the same way! It isn’t even aware that I refactored things a little internally which as a library developer I like. Looking more deeply into this because the compiler actually understands what I am exporting the compile times drop quite dramatically and I can pick and choose exactly what is a part of my interface.

Conclusions

I just pushed a very empty repository to angohr/angohr on GitHub. The first commit shows the initial creation with a few things I didn’t get in to like the presets. The second separates out the class from the module interface and the third adds a license. My aim is to be very minimal in what I add, and to explore fresh approaches using new capabilities of the tools and languages at hand.

The recent trend to header-only C++ libraries has been very much a blessing and a curse where they are so easy to include but compile times explode. Building out better tooling to create and distribute C++ libraries is needed, I have been exploring vcpkg recently as one possible successor to superbuilds. A number of distinct advantages along with many rough edges that is definitely a good subject for a future post.