I recently attended a talk about generating user interfaces from Python, I have fought for and against doing this in various projects. I have also seen places where it really helps and other places where it was a huge detriment (at least in my opinion). The talk got me thinking about how many times how many of us have written our interface generation. At times we also talk about reuse and whether it is worth reusing another approach versus writing our own.

Story Time

First we are going to go way back into ancient history, and one of my first tries encounters with this back during my Google Summer of Code project developing Avogadro and the molecular editor in Kalzium. Avogadro was developed in C++ and one of the primary goals was to be able to build/edit molecules interactively in three dimensions. One of the first things you want to do once you have your molecule is generally to use that structure as input to another code.

To that end we wrote the input generators, these were Qt interfaces developed to take user input and the molecule they had just drawn. They would then generate an “input deck” which I naively just accepted as the local terminology for a long time, it actually refers to punch cards and the way that FORTRAN codes often accept their input. I joked about this when I gave a talk once, exclaiming I had never even touched a punch card myself - a very kind member of the audience had some and gave them to me as a gift!

Anyway, we found that the input generators were very popular. One thing I hadn’t appreciated was the relatively high barrier to entry to create your own. They were written in C++ using Qt, requiring that you set up a development environment, compile Avogadro, add your version by copying one that looked close, do the layout in Qt Designer, and then make a pull request (or submit a patch as we were on Subversion at first). There was also the question of layout uniformity, duplicated code, and what we might do to lower the barrier to contributing/extending input generators.

If you look in the old source code you will see three files per generator, the header, the implementation and the UI file. The positive was that within that generator you could design an interface as simple or as complex as you liked. The negative was quite similar along with having varying levels of appreciation of what else was happening in the broader application. When it came time to develop rewrite Avogadro I thought about how we could make this scale better.

Avogadro Input Generators

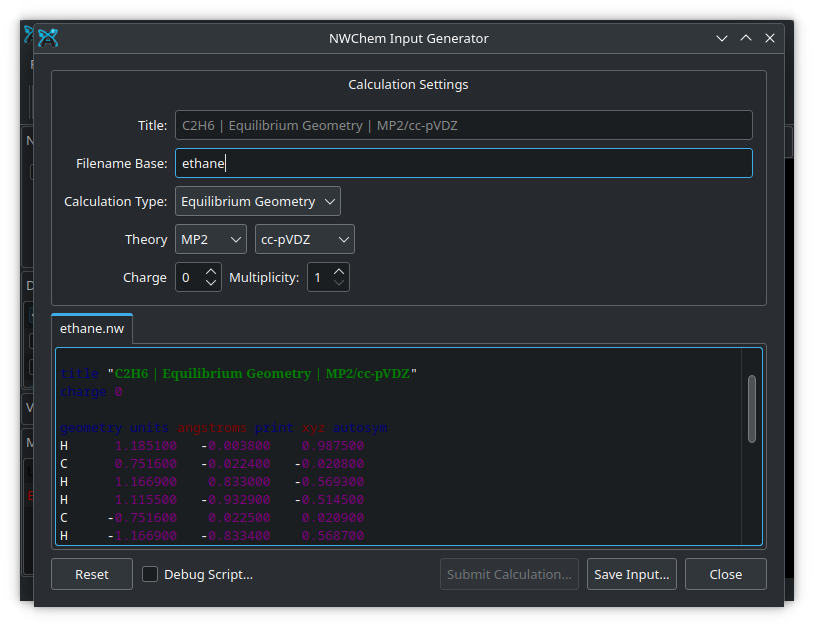

When we were developing Avogadro’s rewrite I really wanted to be able to support a single file per input generator. I also wanted to turn Python on its head to an extent for Avogadro, in the original version the API was wrapped in Python but Avogadro itself couldn’t really leverage Python to extend it. This is where the idea came from to use Python files to specify what their input options were and to generate the appropriate input from the options chosen.

The approach we took was to execute Python from the main C++ process, and ask it for input options using a JSON specification we came up with. It was pretty simple, and concentrated on using a Python dictionary that could easily be written to JSON. That JSON was then used to build the Qt user interface at runtime, and to then submit the options chosen along with the molecule geometry to generate the input file for the code in question.

def getOptions():

userOptions = {}

userOptions['Theory'] = {}

userOptions['Theory']['type'] = "stringList"

userOptions['Theory']['default'] = 1

userOptions['Theory']['values'] = ['RHF', 'B3LYP', 'MP2', 'CCSD']

opts = {}

opts['userOptions'] = userOptions

return opts

There is nothing too surprising in there, each entity declares a type, often with a default, and then some values. There is also support for adding highlighting options so that the generated input benefits from keyword highlighting. The generated input can be edited in place before being submitted and so I wanted an experience close to a code editor when tweaking input files.

At first they started life in the same repository, but after discussions we agreed to separate them out so they could support a different release cadence along with not being mixed up with the larger project. I also had designs on whether they might be general enough to one day generate web interfaces or be used on a server backend to generate input files in bulk. The primary idea was to make them editable by people who may never learn C++ or set up a development environment. If you just want to add a few options locally you can just edit that one file and see the option in the interface.

Tomviz and Generated Interfaces

When we were developing Tomviz I was tempted to do the same thing again, but there was already a well established precedent to use XML files with Python files/other files to generate interfaces in ParaView and ParaView-based projects. I really didn’t want to do XML, and Tomviz was new at the time, so I compromised on using JSON as a way to specify the interface for operators that wanted user input.

You can see documentation for generating interfaces in Tomviz. This keeps the Python code clean, and you can add a file with the same name to add interface. This also has the advantage of not running code to get interface specifications. With the former approach it could be extended to run and store the JSON, but here we just write the JSON directly. It has the same net effect, instead of running the Python you can simply read the JSON if it exists.

{

"name" : "rotation_angle",

"label" : "Angle",

"description" : "Rotation angle in degrees.",

"type" : "double",

"default" : 90.0,

"minimum" : -360.0,

"maximum" : 360.0,

"precision" : 1

}

You can see many of the same concepts but applied in a different domain where things like angles are more important and the range should be constrained. This results in a Qt interface generated at runtime in the C++ code from a constrained specification. This supports effectively allowing a limited number of arbitrary inputs for a Python call where the name becomes the input argument name when the function is called and the value in the user interface is passed to the call site from the C++ side to the Python side.

Hiding Complexity

Behind these specifications and more in many other projects there is a trade off being made. For certain types of interface the uniformity of the interface can really improve usability. When done well they are usually highly focused on a particular domain like options to generate input for a quantum code, or providing a small number of arguments to a Python call. They allow the developer to focus on their task and not get distracted by the complexity of user interface development.

The other side to remember is that they do best when they are highly constrained. The interfaces generated tend to be of the form vertical form with label-input pairs. You have no control over the signal-slot connections a lot of the time, you can only do a limited amount of validation, they look formulaic. When you automatically consume all variables, types, etc they can also become very complex and expose things that don’t make sense or do so in awkward ways.

Happy Medium

In my work I have always found approaches like this to be amazing time savers for contributors, but tend to focus on this a little later in the project life cycle when clear patterns are apparent. There is no replacing a beautiful intuitive interface to interact with software when it is used a lot. Even when automatically generated, you can add guard rails to encourage simplicity and clarity in for the form of the interface.

In some of my current work I am looking at how you can use Python to enumerate the input arguments, types, defaults and other parameters to never even generate a dictionary or write a JSON, YAML or XML file. Offering on-ramps for contributors but also having a clear path to doing this more directly when the simple generated interface is not enough is important in my opinion.

Closing Thoughts

When you decide you want to go down this path you also need to consider the interface you offer the contributor, how can they tweak the generated interface, when are they asking for too much and need to write their own interface, how can you make the generation intuitive and debugging possible. There is often the draw of generality, which also means lowest common denominator versus tightly coupling to your libraries, toolkits, application and domain.